Mapping the Unseen

How Professor Fernandez-Diaz and NCALM Help

Unearth Hidden Mysteries

Professor Juan Carlos Fernandez-Diaz is passionate about his groundbreaking work in airborne laser mapping. Also known as LiDAR, this technique uses lasers to obtain highly accurate and high-definition 3D maps of the Earth’s surface. These unique maps prove integral to the research of countless scientists. What excites Professor Fernandez-Diaz most about his work are these interdisciplinary connections.

“We have supported researchers from fields like archaeology, ecology, forestry, geology, geophysics, glaciology, hydrology, zoology and more,” he shares.

Professor Fernandez-Diaz and his team run a research center called the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping. The center’s most notable and visible work has been archaeological explorations and mapping in Mexico and Central America since 2009. University of Houston’s new Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Diane Z. Chase used these maps in her work as an archaeologist in the Mayan site Caracol located in Belize. She is very impressed with their work.

“The LiDAR that NCALM created transformed and continues to transform our archaeological research,” Provost Chase says, “allowing us to answer questions about ancient Mayan life that we would previously not have dreamed possible.”

The research center’s work may be cutting-edge, but NCALM has actually been around for 20 years, starting from a grant given from the National Science Foundation in 2003. Initially, the center was a collaboration between researchers at the University of Florida and the University of California, Berkeley. In 2010, the researchers from the University of Florida moved to their current home at University of Houston. With the continued support from NSF, the center has been productive.

“We have mapped tens of thousands square kilometers of topography all over the continental USA, Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and destinations as remote as New Zealand and Antarctica,” Fernandez-Diaz explains.

This past year, an anonymous donor contributed a generous gift to support the center and Professor Fernandez-Diaz’s work. When asked what inspired them to give, they pointed to the quality and impact of Fernandez-Diaz’s work.

“After retiring from the tech industry, I turned my attention to research in the area of the ancient Maya. As part of the Chactún Project with Dr. Ivan Sprajc, I was introduced to Professor Fernandez-Diaz and his team. Juan breathed life into the complex process of aerial laser mapping and its emerging utilization in field archaeology. Through these conversations, it became clear that LiDAR would expedite and improve our work at Chactún and future projects. This turned out to be an understatement,” the donor shares enthusiastically. “With the LiDAR images for Chactún, we were able to perform over a decade’s worth of on-the-ground research in a single field season. I was pleased to be in a position to donate resources that enables Juan’s team to support archaeologists’ quest to answer age-old questions about the ancient Maya.”

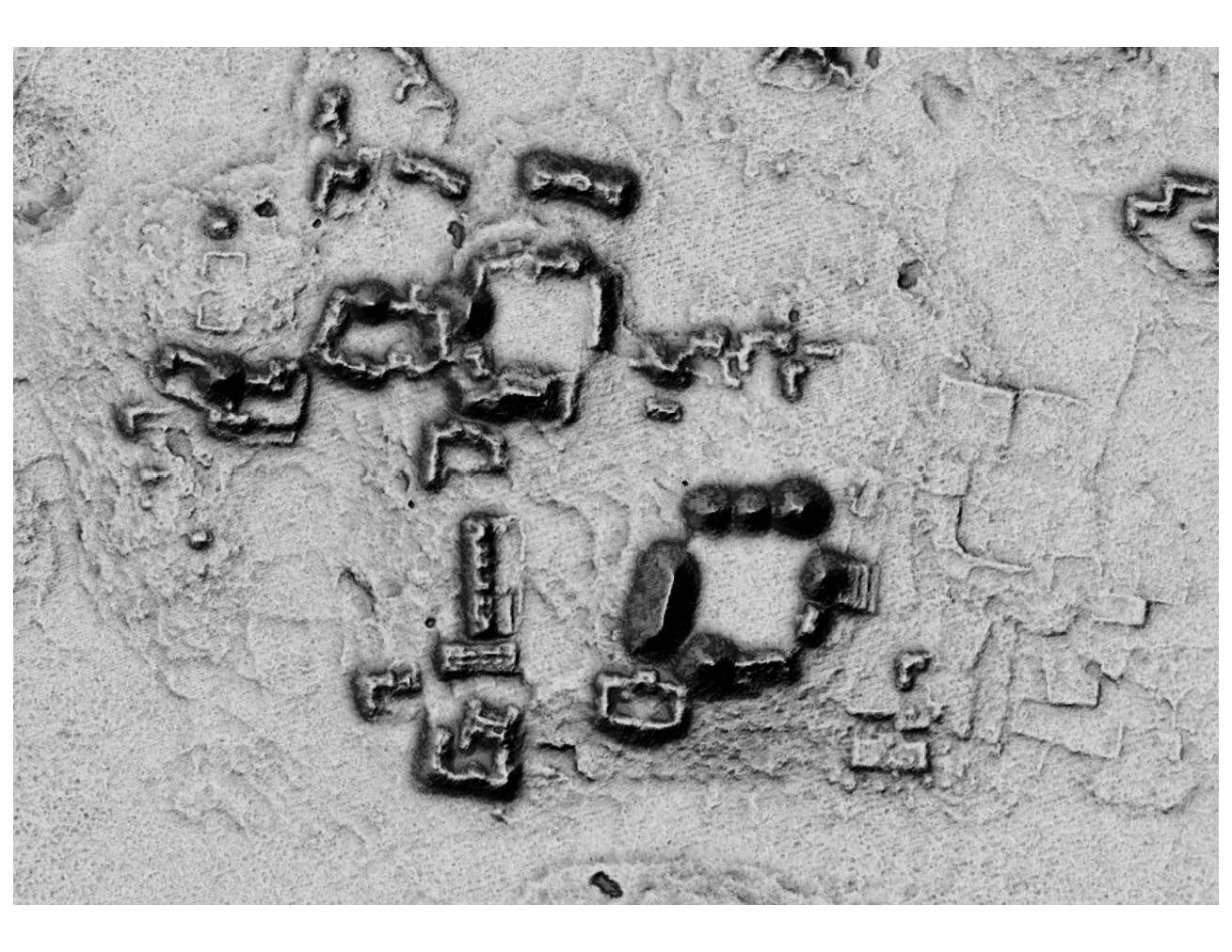

The following two images show how laser detection and imaging produce much more informative maps than a traditional satellite image. The first image is from Google Earth. The second photograph is from NCALM, courtesy of the Chactún Project.

This is a traditional satellite image from Google Earth of the forest where the ancient Maya lived.

This is a traditional satellite image from Google Earth of the forest where the ancient Maya lived.

This is the LiDAR image of the same forest from NCALM, courtesy of the Chactún Project.

This is the LiDAR image of the same forest from NCALM, courtesy of the Chactún Project.

While Fernandez-Diaz very much appreciates the funding he’s received from the government, he emphasizes the special significance of donor support: “What is important and unique about donor support is that it allows us to do research that would be considered too high risk for traditional funding agencies. Through donor support, we have been able to do a few shot-in-the-dark types of surveys, where we can map and explore places that are truly and completely uncharted and unknown. This type of support has produced incredible discoveries, such as the Ciudad del Jaguar in Honduras in 2012, the Ocomtún in Campeche, Mexico in 2023 and others that are yet to be announced.”

This donor hopes their support encourages Professor Fernandez-Diaz to pursue more of the research he personally wants to do. “Let the scientists use the money to figure out how to get the best results. No strings attached. When I donated, I said, ‘Juan, go! Go do your thing!’”

In addition to research, the center also trains graduate students in this airborne light detection and ranging. They will be the next generation of researchers equipped to meet the needs of academic institutions, government agencies and private industry.

Professor Fernandez-Diaz joined the 2023-2025 cohort for the American Geophysical Union LANDInG Academy Fellows. The LANDInG Academy is a two-year program aimed at providing faculty with the tools, network and resources to achieve a more balanced representation in geosciences. He wants to contribute to the future of LiDAR mapping, making sure the future is inclusive and equitable.

Professor Fernandez-Diaz understands the complexity of his role at the helm of his “small but excellent team.” Looking towards the future, he advises his students that “To be successful in an academic setting, it is not only important to do rigorous research and obtain grants from traditional funding agencies but also to be able to tell a good story that is exciting and compelling to the general public. They are the ones who, through their taxes or their donations, support the work you want to do.”

Diaz-Fernandez and his team’s work not only tells a compelling story that inspires people to get involved, but it also serves as a catalyst for many other important stories to unfold.